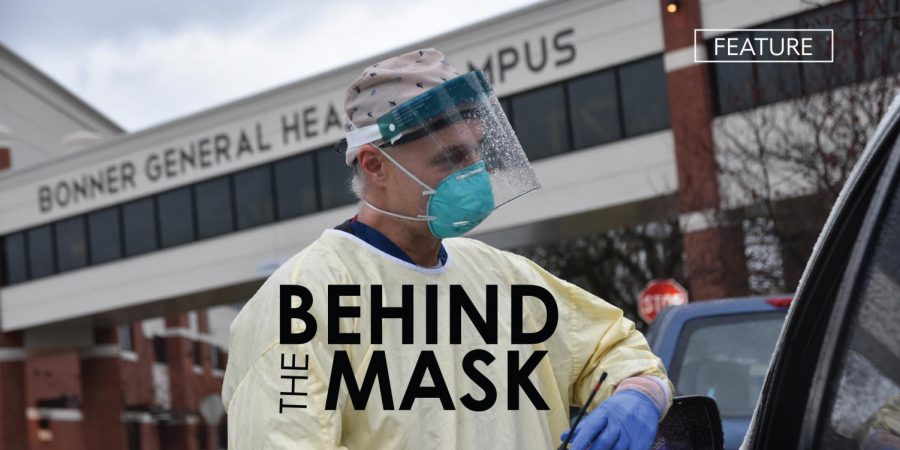

Behind the Mask

A look into what it is like working on the frontlines of COVID-19

Exhausted from traveling, the emergency medicine physician, Tricia Dickens, roamed the El Paso International airport. She was surrounded by individuals suited up in masks who were booking flights to escape COVID-19. The reality of how severe the pandemic was in this city hit her. As a traveling physician, she wanted to go where she was most needed–and for the next several weeks, it would be El Paso, Texas.

Since 2017, Dickens has been a traveling physician licensed in emergency medicine in 6 states. As COVID-19 spread rapidly and hospitals overflowed, Dickens was assigned to cities across the country whose health care facilities desperately needed extra hands. The national shortage of healthcare professionals to attend to the abundance of patients entering the hospitals was so urgent that Dickens was flown out to states that she didn’t even have a license in such as New York, Arizona, and Texas. There was no time to waste applying for a lice

nse in the middle of a crisis.

An average day in Dickens’ life is intense. Just reviewing each patient’s condition with the nurses would take her up to half the day. The rest of her day is filled with completing procedures that need to be done. “There’s no idle time,” Dickens said, “I’m either working, eating, or sleeping” Dickens works anywhere from 6 to 12 “shifts” throughout the year, with each shift being several weeks long.

It is nearing 10 months since the first pandemic hit the United States, yet it is still too early to identify the patterns of the Coronavirus. Viruses are complicated and unpredictable. This has been a source of anxiety for people across the nation. “Our society is so used to immediate answers to everything, that uncertainty…doesn’t feel good,” Dickens said.

Even physicians do not fully understand the extent of the virus as they have been bombarded with so much new information in such a short period of time. Dickens made a point that the public needs to be patient and understanding with health care professionals since they are still figuring out how to overcome the pandemic. “We don’t come across something completely novel and know exactly how it all works.” Dickens emphasized, “We have to have experience with it first.”

What is different about the Coronavirus is that it impacts other organ systems besides the respiratory system even in patients with no preexisting medical conditions. Dickens explained, “It’s amazing to me that this is a respiratory virus…This one is creating a blood issue so it’s not just a respiratory issue. That includes the clotting system and the inflammatory system in our body and creates significant issues in our other organs that are not typically affected by a respiratory infection.” This aspect of the novel virus has been eye-opening to physicians who have never encountered something like it before.

“I have a respect for the virus that I think a lot of people who haven’t experienced a loved one that became ill with it would have no concept of,” Dickens said. She stands by patients’ sides and watches their health rise and fall in hopes that everything she has done to care for them is enough to save their lives. “That’s very rewarding to watch someone on the brink of death and watch them improve.” Dickens said, “It’s a feeling that you just never forget”

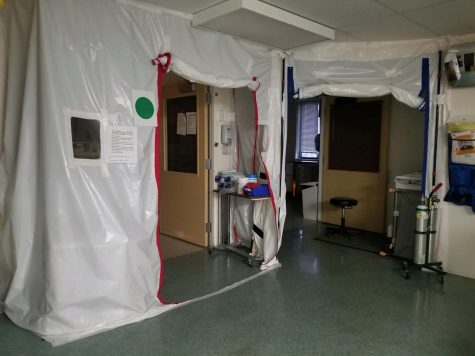

Shane May, a nurse at MultiCare Deaconess Hospital in Spokane, Washington, said that his day to day intensive aftercare of COVID patients is time-consuming. He stays busy treating the patients’ other health concerns that couple with the virus such as Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and pneumonia. He explained that it is a process to enter the room of a COVID patient and the team has to have a plan and suit up in protective gear such as a PAPR (Powered Air Purifying Respirator). Many hospitals, including Deaconess, have altered the airflow of COVID patients’ rooms so that contaminated air does not circulate through the rest of the hospital when the door is opened.

May contracted COVID and experienced all the common flu-like symptoms except for a fever. He observed that not developing a fever was a trend in most of the COVID patients he treated. May had to quarantine for 10 days and could only go back to work after being symptom-free for a full 48 hours. With practice in conducting COVID tests, May found that tests are not always reliable since “People that contract COVID can test positive kind of on and off for a while and so it would make the test erroneous.” he said.

Dealing with COVID patients has been a learning experience for nurses and physicians across the nation. For May, becoming more familiar with ventilators, machines that help breathe for patients was a critical learning curve. “It’s difficult to optimize the vent settings…” May said, “[and] find the happy place that best oxygenates the patient and there’s a type of different style to protect their lungs.” In some cases, even if putting a patient on a ventilator is the only method of care that w

ill keep them alive, it is a struggle for their body to keep up with the stress of their treatment changing.

In Bonners Ferry, community member Tracey Koch practices nursing at the Kootenai Tribal Clinic. “It’s been a real challenge, as far as the clinic is concerned, to really make sure that we’re available for everyone and that people have access to care,” she said, “but yet we have to think about the big picture and keep everybody safe.” The clinic has had to undergo a lot of procedural changes to make the facility safer such as letting only a certain number of patients into the building at a time. They also engage in “telemedicine” where patients can seek help over the phone to minimize the number of people coming to the clinic in person.

Nursing Supervisor, Sharon Bistodeau, has devoted 28 years of her life to working at Bonner General Hospital in the ER, ICU, and anywhere else she is needed. As a smaller hospital, Bonner General is staffed according to a 25-bed hospital so they do not have an abundance of extra hands. There has been a nationwide shortage of nurses for years, and more so now than ever because of the intensity in hospitals because of COVID is too much for some nurses to stay in the practice. But not for Bistodeau.

Caring for COVID patients is more time and resource-consuming. “There are a whole plethora of people that take care of one patient,” Bistodeau said. Because the disease is so contagious, nurses who care for COVID patients have to be isolated to the COVID pods–the area sanctioned specifically for the individuals who contract the Coronavirus. Many healthcare professionals have had to step away from their specialties to be on the frontlines of COVID which is mentally and emotionally draining.

Today’s technology has helped connect people but still does not offer the same feeling as holding the hand of a sick loved one. This disease is not only physically taxing, but has a major psychological impact on both patients and hospital staff. “Patients are put in rooms by themselves without family coming to visit,” Bistodeau said.“I know nurses that are the strongest nurses I’ve ever met in my whole life and they break down and bawl because of this.”

If you were to come into the hospital as a COVID patient, you would be isolated with no family members or visitors. “These patients are scared. They don’t have anybody’s hand to hold except for our hand that has a glove on it.” Bistodeau said when painting a picture of what a COVID patient experiences. “You’re masked up and they don’t even know who you are…Nobody can see your smile. Nobody can see your tears.” This aspect is heartbreaking for the nurses who directly come in contact with the individuals who have COVID.

Erin Binnall, the Manager of Community Development and Public Information Officer for Bonner General Health wants people to feel safe coming to the hospital. “We don’t want to scare people away either because people need routine medical care.” she said, “People are having heart attacks, they’re having strokes, there are traumas, and we’re still here to service them.” Binnall feels that this is why people must practice personal responsibility and be mindful of others so those in need of medical care can get the attention they need.

Bistodeau emphasized that the most effective way to protect yourself and others from the virus is by washing your hands and wearing a mask. “You’re a hero by putting that mask on,” Bistodeau said. “We need to quit politicizing this stuff. It’s a healthcare issue.” Binnall stressed that the Coronavirus is undeniably real and is not something that should not be ignored by young people. “We are caring for younger, middle-aged individuals who have had no comorbidities, are in ICU, and have been in ICU for over 2 weeks,” Binnall said, putting the seriousness of the disease in perspective. “It hits anybody differently,” she said, “You don’t know how it’s going to affect anybody”

According to Panhandle Health Districts data, in the last five years, there have been less than 60 deaths caused by the flu in the region, whereas there have been over 90 deaths caused by the Coronavirus in the last 8 months. COVID has caused hospitals around the country to be overwhelmed and at maximum capacity. Every bed in Bonner General Health’s COVID pod is full with only a few beds available in the whole hospital at a time. If the regional hospitals such as Kootenai Health and Sacred Heart reach maximum capacity, Bonner General has nowhere to send their patients, so they have to do their best to treat them whether they have the capabilities to care for them or not.

“I think now more than ever, our healthcare community and our health care workers need community support,” Binnall said. From when COVID was just beginning, to now reaching over 200 cases in the region, health care professionals have needed support and understanding from the community. “Now is the time where we need to pull together and be there for one another and be mindful and be kind and be the wonderful small Bonner County community that we’ve always been.”

What weird sound do you love?

I love the sound of a crackling fire. It reminds me of summer campfires and cozy winter nights at the same time.

What...