The pen has always been mightier than the sword—and without a doubt, it remains the most powerful tool that rests in the Oval Office. Lately, however, it hasn’t been resting. In the hands of the president, a single signature can reshape national policy in an instant. The Trump administration has put this power to the test, issuing approximately 45 executive orders since his inauguration. By the end of Tuesday, that number is expected to rise to nearly 50—potentially making it the most executive orders signed by any president within their first 100 days in office (with the exception of FDR).

Some of these orders have made national and international headlines, such as imposing a 25% tariff on Mexico and Canada (set to be revisited in 30 days) and an additional 10% tariff on certain Chinese imports. Others have focused on policy shifts, including withdrawing from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Paris Climate Agreement. Some have been symbolic—such as renaming the Gulf of Mexico to the “Gulf of America”—while others have been procedural, including first-day executive orders that rescinded 78 orders from the previous administration, many of which were related to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Several of these orders have also been met with scathing criticism and legal challenges. The executive order to end birthright citizenship, for example, was temporarily blocked and is currently being challenged by the ACLU and multiple federal judges. Largely because the 14th Amendment grants citizenship to anyone born on U.S. soil, to change this, the Constitution would have to be amended, and the president alone can’t do that. It would need to involve both state legislators and Congress. Another order, which aimed to freeze federal funding for various programs, has since been rolled back, as Congress typically controls appropriations.

Executive orders are written initiatives/directives signed by the government to take certain actions. In addition to reframing policy, executive orders can guide the government in how to interpret and enforce the law. Executive orders first started being numbered by the Department of State in 1907, and they went back and numbered all of them in 1862. Executive orders are not legislation, and the two should never be confused. The president can not by any means be involved in creating legislation. That is Congress’s job. Executive orders might hold the same weight as law, but they are not. They require no approval from Congress. Executive orders cannot overturn the law. Congress cannot overturn them, but they can pass legislation that makes enacting them near impossible. Regardless, just like any Government position, the president is bound by the constitution, and so are their executive orders.

Executive orders have been a favorite tool of governance in the executive branch for some time (FDR issued nearly 307 a year). However, the frequency and scope of them under the Trump Administration have reignited debates over presidential power. Understanding their impact requires taking a far deeper look into their legal foundations, historical precedent, and potential implications in years to come.

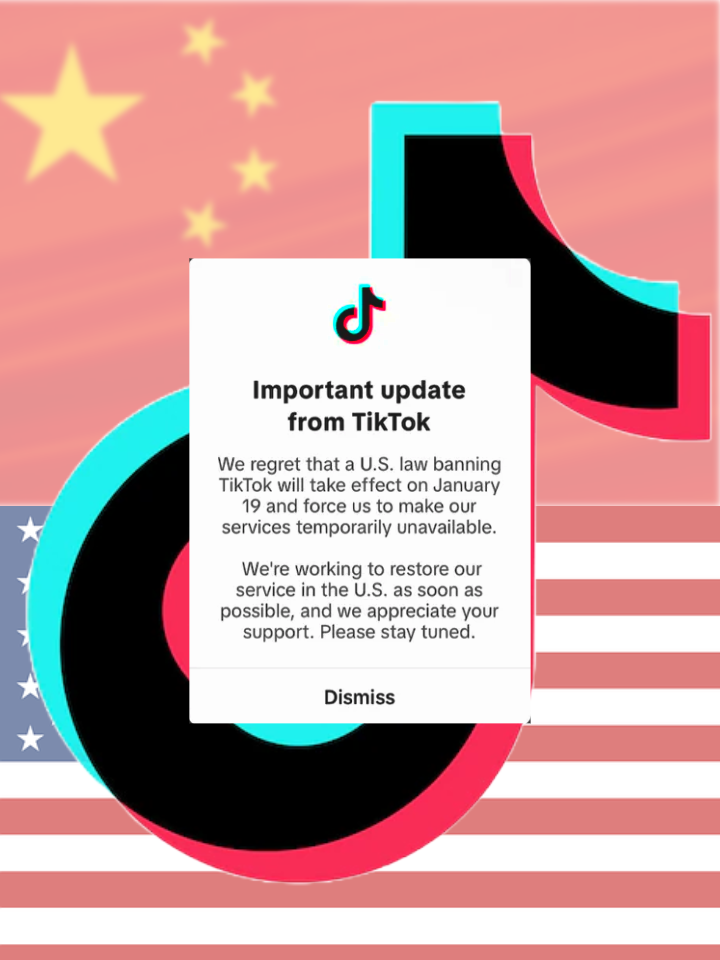

To gain a better understanding of these nuances, I spoke with one of SHS’s government teachers, Brian Smith. The first thing that needed explaining was the scope of executive orders and how they differ from law . Smith says they end up “weighing law”; however, he also explains that executive orders have to “stem from some authority, either granted by law or the constitution itself.” For example, the executive order that brought TikTok back for the 90 extension was already an executive order outlined in the law that banned the app. The power of recognition (to recognize which countries exist and which don’t) is granted to the president constitutionally, so Trump renaming the Gulf of Mexico was perfectly legal.

Smith also notes that “again, they’re often controversial, if it’s an area congress feels like they should be legislating as opposed to the president.” Take, for example, the freezing of federal funds. The budget is something typically Congress is in charge of, so this was quickly shot down. Mr. Smith went on to tell me that likely one of the most controversial Executive orders was FDR’s Executive Order 9066, which put 120,00 Japanese Americans in internment camps on February 19th, 1942 (10 weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor). They were held there until 1946, when Truman issued 9742, which dissolved the internment program.

Even in recent years, Executive orders from Modern presidents have been extremely controversial. Biden’s most controversial executive order was requiring federal employees and contractors to get the Covid-19 vaccine. Obama’s most controversial was an executive order that provided immigrants who had been brought here as children temporary protection from deportation (DACA). Bush’s most controversial was an executive order that allowed religious institutions to receive funding for social services.

Executive orders have also been the sole reasons for some of the most important and proudest moments of our history. The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order, Executive Order 9981 desegregated the armed forces, and Executive Order 10924 was responsible for setting up the Peace Corps.

Trump shows no signs of putting down the most powerful tool in government (the pen) anytime soon. If you are curious about his executive orders or any of the ones from the past, please check out https://www.federalregister.gov/. All Executive orders are labeled and numbered and easy to view and read in full there. Regardless of your political affiliation, executive orders are a gigantic part of this new administration, and it is imperative to stay up to date on the state of our nation.